Tilting, but not at windmills…

books, business and economy, comics and animation, cyberpunk/steampunk, cycling, environment, event, everyday glory, family and friends, food for thought, health, history, movies and TV, politics and law, science and technology, sports, style and fashion, The Covet List, the world, trains/model railroads No Comments »Thursday – 09 February 2012

This NBN Thursday is a bit grey and hazy. But, I started the morning with SaraRules! and the girls, so it was a good kick-off to the day.

Last night, we watched Killer Elite (not to be confused with the movie with almost the same title from 1975) for Movie Date Night. Robert DeNiro. Clive Owen. Jason Statham. All kicking ass and, in some cases, taking names. The premise was a little different than I expected, but not in a bad way. There were a couple of plot holes, but what movie doesn’t have those these days? In the end, it made for a decent night’s viewing.

Also, I tried out something different with my bike trainer: Disengaging the tension wheel, so that the back wheel spun freely. Works, but without any resistance, I was pedaling as easily in the higher gears (15 and up) as I was in the first three gears. Still, it’s an option.

Chew on This: Food for This – Black History Month

Today, you’re getting a double d0es of Black History Month goodness.

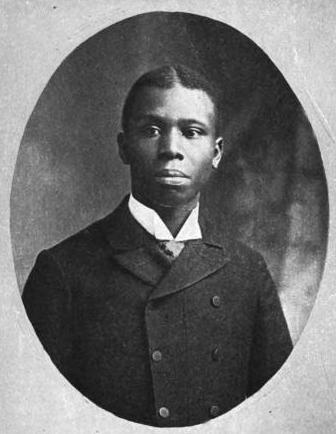

- The first person of note is James Weldon Johnson, author, politician, poet, songwriter, and educator, and early civil rights activist.

![[James-Weldon-Johnson,-half-length-portrait,-facing-front]-LOT-13074,...-painting-artwork-print](http://blog.echopulse.net/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/James-Weldon-Johnson-half-length-portrait-facing-front-LOT-13074...-painting-artwork-print.jpg) James Weldon Johnson (June 17, 1871 – June 26, 1938) was born in Jacksonville, Florida, the son of Helen Louise Dillet and James Johnson. His brother was the composer J. Rosamond Johnson. Johnson was first educated by his mother (the first female, black teacher in Florida at a grammar school) and then at Edwin M. Stanton School. At the age of 16 he enrolled at Atlanta University, from which he graduated in 1894. In addition to his bachelor’s degree, he also completed some graduate coursework there.

James Weldon Johnson (June 17, 1871 – June 26, 1938) was born in Jacksonville, Florida, the son of Helen Louise Dillet and James Johnson. His brother was the composer J. Rosamond Johnson. Johnson was first educated by his mother (the first female, black teacher in Florida at a grammar school) and then at Edwin M. Stanton School. At the age of 16 he enrolled at Atlanta University, from which he graduated in 1894. In addition to his bachelor’s degree, he also completed some graduate coursework there.

After graduation he returned to Stanton, a school for African American students in Jacksonville, until 1906, where, at the young age of 23, he became principal. As principal Johnson found himself the head of the largest public school in Jacksonville regardless of race. Johnson improved education by adding the ninth and tenth grades. During his tenure at Stanton, Johnson wrote Lift Every Voice and Sing — often called “The Negro National Hymn”, “The Negro National Anthem”, “The Black National Anthem”, or “The African-American National Anthem” — set to music by his brother John Rosamond Johnson (1873–1954) in 1900.

In 1897, Johnson was the first African American admitted to the Florida Bar Exam since Reconstruction. He was also the first black in Duval County to seek admission to the state bar. In order to receive entry, Johnson underwent a two-hour examination before three attorneys and a judge. He later recalled that one of the examiners, not wanting to see a black man admitted, left the room.

In 1906 President Theodore Roosevelt appointed him U.S. consul to Puerto Cabello, Venezuela, and in 1909 he became consul in Corinto, Nicaragua, where he served until 1914. He later taught at Fisk University. Meanwhile, he began writing a novel, The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man (published anonymously, 1912), which attracted little attention until it was reissued under his own name in 1927.

In 1920 Johnson was elected to manage the NAACP, the first African American to hold this position. While serving the NAACP from 1914 through 1930 Johnson started as an organizer and eventually became the first black male secretary in the organization’s history. In 1920, he was sent by the NAACP to investigate conditions in Haiti, which had been occupied by U.S. Marines since 1915. Johnson published a series of articles in The Nation, in which he described the American occupation as being brutal and offered suggestions for the economic and social development of Haiti. These articles were reprinted under the title Self-Determining Haiti. Throughout the 1920s he was one of the major inspirations and promoters of the Harlem Renaissance trying to refute condescending white criticism and helping young black authors to get published.

Johnson died while vacationing in 1939, when the car he was driving was hit by a train.

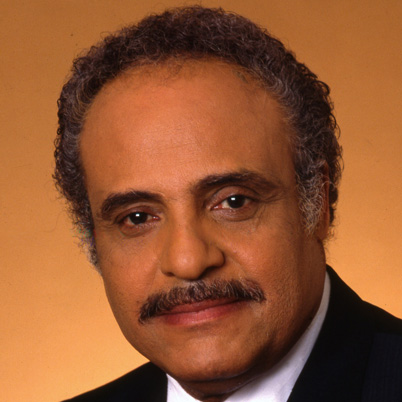

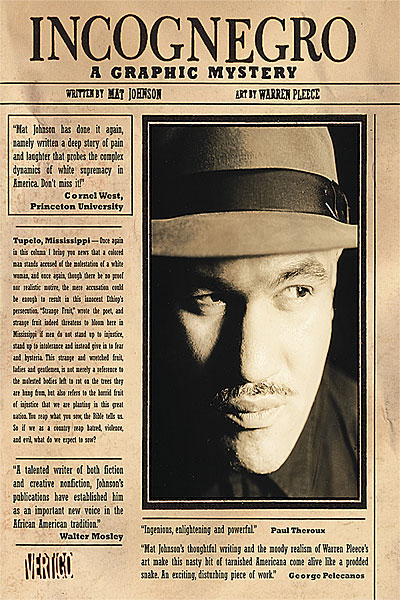

- The second person of note is Mat Johnson (no relation), an American writer of literary fiction.

Johnson (born August 19, 1970) grew up in “racially stratified” Philadelphia. His mother is African American; his father, Irish American. After his parents’ divorce, he was raised by his social worker mother in a largely black section of the city, Germantown, where he often felt like a standout. “When I was a little kid, I looked reallywhite—I was this little Irish boy in a dashiki.”In his teens, he transferred to a private school, Abingdon Friends, in a more affluent neighborhood. “It was the first time I was around a lot of white people. I suddenly realized I had an ethnic identity, and started to think about race.” He listened to Public Enemy and devoured The Autobiography of Malcolm X and books by W.E.B. DuBois and Toni Morrison. “African-American literature felt like an intellectual home, this place where I fit and belonged,” he says gratefully.

Johnson (born August 19, 1970) grew up in “racially stratified” Philadelphia. His mother is African American; his father, Irish American. After his parents’ divorce, he was raised by his social worker mother in a largely black section of the city, Germantown, where he often felt like a standout. “When I was a little kid, I looked reallywhite—I was this little Irish boy in a dashiki.”In his teens, he transferred to a private school, Abingdon Friends, in a more affluent neighborhood. “It was the first time I was around a lot of white people. I suddenly realized I had an ethnic identity, and started to think about race.” He listened to Public Enemy and devoured The Autobiography of Malcolm X and books by W.E.B. DuBois and Toni Morrison. “African-American literature felt like an intellectual home, this place where I fit and belonged,” he says gratefully.

Like the late playwright August Wilson, Johnson seems to identify almost exclusively with the African roots of his biracial family tree. “African-American is a Creole culture. It embraces the mix,” he asserts.

Mat Johnson attended West Chester University, University of Wales-Swansea, and ultimately received his BA from Earlham College, and in 1993, he was awarded a Thomas J. Watson Fellowship. Johnson received his MFA from Columbia University School of the Arts in 1999. Johnson has taught at Rutgers University, Columbia University, Bard College, The Callaloo Journal Writers Retreat, and is now a permanent faculty member at The University of Houston Creative Writing Program.

Mat Johnson’s first novel, Drop (Bloomsbury USA in 2000), was a coming of age novel about a self-hating Philadelphian who thinks he’s found his escape when he takes a job at a Brixton-based advertising agency in London, UK. Drop was listed among Progressive Magazine’s “Best Novels of the Year.” In 2003, Johnson published Hunting in Harlem (Bloomsbury USA 2003), a satire about gentrification in Harlem and an exploration of belief versus fanaticism. Hunting in Harlem won the Zora Neale Hurston/Richard Wright Legacy Award for Novel of the Year.

Johnson made his first move into the comics form with the publication of the five-issue limited series Hellblazer Special: Papa Midnite (Vertigo 2005), where he took an existing character of the Hellblazer franchise and created an origin story that strove to offer depth and dignity to a character that was arguably a racial stereotype of the noble savage. The work was set in 18th Century Manhattan, and was based around the research that Johnson was conducting for his first historical effort, The Great Negro Plot, a creative non-fiction that tells the story of the New York Slave Insurrection of 1741 and the resultant trial and hysteria.

In February 2008, Vertigo Comics published Johnson’s graphic novel Incognegro, a noir mystery that deals with the issue of passing (racial identity) and the lynching past of the American south.

He was named a 2007 USA James Baldwin Fellow and awarded a $50,000 grant by United States Artists, a public charity that supports and promotes the work of American artists. On September 21, 2011, Mat Johnson was awarded the Dos Passos Prize for Literature.

Information courtesy of Chronogram.com, DCComics.com, matjohnson.info and Wikipedia

Stray Toasters

- I’d like to add this to The Covet List.

- …and an order of these, too.

- Retro Fitted

- I drew some tweets, by The Oatmeal

- Try Medieval Hot Pants? Surely, You Joust

Well, I don’t… but it is my home state’s official state sport.

- States Negotiate $26 Billion Agreement for Homeowners

- I like this Project: Rooftop redesign of the X-Men’s White Queen’s outfit.

- Steampunk Magazine is back!

- China police chief may seek U.S. asylum

- MINE!

I had to order this. Compelled to, I say! It’s the location of Beth Steel that my father used to work for. - US Approves Two New Nuclear Reactors

- The science-fiction effect

- Tai Chi May Help Parkinson’s Patients Regain Balance

Namaste.