“You say you want a revolution? Well, you know, we all want to change the world.”

art, books, business and economy, comics and animation, football, games, health, history, LEGO and Rokenbok, movies and TV, music, science and technology, style and fashion, The Covet List, the world, trains/model railroads, travel February 3rd, 2011Thursday – 03 February 2011

It’s my NBN Technical Friday. Amen.

Last night was D&D (4.0) game night with

I also played a little DCUO last night. I’m still having a lot of fun with it. Last night, I was sent to a new (to me) part of Metropolis, Chinatown, to meet Zatanna for my next set of missions. Let me just say that this part of the city looks simply amazing. The DCUO team also released another teaser video that portends ill things…

AND… new information has been released about new content being added to the game, including their Valentine’s Day event content, as well.

Chew on This: Food for Thought – Black History Month

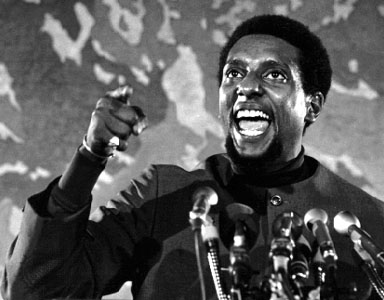

Today’s personality is: Stokely Carmichael

Kwame Ture, also known as Stokely Carmichael, was a Trinidadian-American black activist active in the 1960s American Civil Rights Movement. He rose to prominence first as a leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced “snick”) and later as the “Honorary Prime Minister” of the Black Panther Party. Initially an integrationist, Carmichael later became affiliated with black nationalist and Pan-Africanist movements. He popularized the term “Black Power”.

In 1960, Carmichael went on to attend Howard University, a historically-black school in Washington, D.C., rejecting scholarship offers from several white universities. His apartment on Euclid Street was a gathering place for his activist classmates. He graduated with a degree in philosophy in 1964.

He joined the Nonviolent Action Group (NAG), the Howard campus affiliate of SNCC. He was inspired by the sit-ins to become more active in the Civil Rights Movement. In his first year at the university, he participated in the Freedom Rides of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and was frequently arrested, spending time in jail. In 1961, he served 49 days at the infamous Parchman Farm in Sunflower County, Mississippi. He was arrested many times for his activism. He lost count of his many arrests, sometimes giving the estimate of at least 29 or 32, and telling the Washington Post in 1998 he believed the total number was fewer than 36.

Carmichael saw nonviolence as a tactic as opposed to a principle, which separated him from moderate civil rights leaders like Martin Luther King, Jr.. Carmichael became critical of civil rights leaders who simply called for the integration of African Americans into existing institutions of the middle class mainstream.

The Black Panthers and Carmichael disagreed on whether white activists should be allowed to help the Panthers. The Panthers believed that white activists could help the movement, while Carmichael thought as Malcolm X, saying that the white activists needed to organize their own communities first. In 1969, he and his then-wife, the South African singer Miriam Makeba, moved to Guinea-Conakry where he became an aide to Guinean prime minister Ahmed Sékou Touré and the student of exiled Ghanaian President Kwame Nkrumah. Makeba was appointed Guinea’s official delegate to theUnited Nations. Three months after his arrival in Africa, in July 1969, he published a formal rejection of the Black Panthers, condemning the Panthers for not beingseparatist enough and their “dogmatic party line favoring alliances with white radicals”.

It was at this stage in his life that Carmichael changed his name to Kwame Ture to honor the African leaders Nkrumah and Touré who had become his patrons. At the end of his life, friends still referred to him interchangeably by both names, “and he doesn’t seem to mind.”

Carmichael remained in Guinea after separation from the Black Panther Party. He continued to travel, write, and speak out in support of international leftist movements and in 1971 collected his work in a second book Stokely Speaks: Black Power Back to Pan-Africanism. This book expounds an explicitly socialist, Pan-African vision, which he seemingly retained for the rest of his life. From the late 1970s until the day he died, he answered his phone by announcing “Ready for the revolution!”

Stray Toasters

- This LEGO video was sent to my by angstd:

- Shippers Concerned Over Possible Suez Canal Disruptions

- The White Stripes Call It Quits

- The Super Bowl is Sunday. As the Ravens (and Dolphins and Panthers) are not in the game, I guess this means that I’m a Packers fan… at least through the weekend.

- Even the Avengers are choosing sides… again:

- Even the Avengers are choosing sides… again:

- Ad banned for simulating drug use

- MTH has announced a locomotive that I now covet.

I specifically want it in the Army livery. - Reprogrammed stem cells are loaded with errors

- LEGO Mystery Box

- Dispute Over Jewish Archives Derails Russian Art Loans to U.S.

- Classic Teen Heroes Boogie Down in the Art of Bill Walko

- This is a very cute commercial:

- The time has come for child seats on airplanes

- Foreclosed Homeowners Go to Court on Their Own

Namaste.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.