Catching up – Black History Month 2014 (continued)

event, everyday glory, food for thought, history February 24th, 2014Monday – 24 February 2014

This month’s kind of gotten away from me, but I’m staging a comeback. Of sorts.

Chew on This: Food for Thought – Black History Month

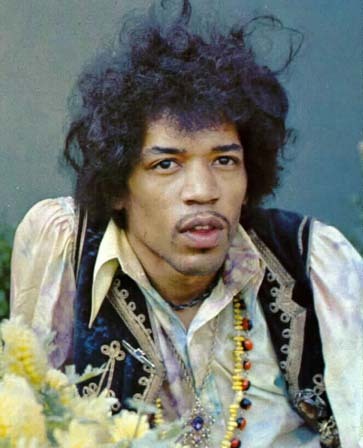

- Jimi Hendrix – James Marshall “Jimi” Hendrix (born Johnny Allen Hendrix; November 27, 1942 – September 18, 1970) was an American musician, singer, and songwriter.

Despite a brief mainstream career spanning four years, he is widely regarded as one of the most influential electric guitarists in the history of popular music, and one of the most celebrated musicians of the 20th century. The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame describes him as “arguably the greatest instrumentalist in the history of rock music.”

A fan of blues music, Hendrix taught himself to play guitar. At the age of 14, Hendrix saw Elvis Presley perform. He got his first electric guitar the following year and eventually played with two bands—the Rocking Kings and the Tomcats. In 1959, Hendrix dropped out of high school. He worked odd jobs while continuing to follow his musical aspirations.Hendrix enlisted in the United States Army in 1961 and trained at Fort Ord in California to become a paratrooper. Even as a soldier, he found time for music, creating a band named The King Casuals. Hendrix served in the army until 1962 when he was discharged due to an injury.

In mid-1966, Hendrix met Chas Chandler—a former member of the Animals, a successful rock group—who became his manager. Chandler convinced Hendrix to go to London where he joined forces with musicians Noel Redding and Mitch Mitchell to create The Jimi Hendrix Experience. While there, Hendrix built up quite a following among England’s rock royalty.

Released in 1967, the band’s first single, “Hey Joe” was an instant smash in Britain, and was soon followed by other hits such as “Purple Haze” and “The Wind Cried Mary.” On tour to support his first album, Are You Experienced? (1967), Hendrix delighted audiences with his outrageous guitar-playing skills and his innovative, experimental sound.

Hendrix died on September 18, 1970, from drug-related complications. While this talented recording artist was only 27 years old at the time of his passing, Hendrix left his mark on the world of rock music and remains popular to this day. As one journalist wrote in the Berkeley Tribe, “Jimi Hendrix could get more out of an electric guitar than anyone else. He was the ultimate guitar player.”

- Indentured Servitude (or “bonded servitude”) was a form of contract labor most often associated with the labor supply of the English colonies in North America during- the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Generally speaking, there were two rather broad categories of indentured servants in colonial America: voluntary servants (often called “redemptioners”) and involuntary servants.

Redemptioners were those British and western Europeans who literally sold themselves for limited terms of labor service (usually three to seven years) in exchange for ship passage to the colonies.Involuntary servants, on the other hand, included individuals kidnapped by shipmasters in Europe and then sold at the end of the Atlantic voyage, as well as convicts from English prisons whose sentences were commuted into specific lengths of labor service (usually five to fourteen years) in the colonies.

The twenty Africans who landed at Jamestown, Virginia in 1619 were indentured servants, not slaves. Although it is true that black indentured servitude (unlike white indentured servitude) ultimately evolved into a system of chattel slavery, it is incorrect to assume that slavery automatically began in the English colonies the moment these twenty blacks stepped ashore. To the contrary, this group of Africans was merely absorbed into the prevailing indentured servitude labor system which existed in early seventeenth century Virginia.

- Scott Joplin (c. 1867/1868? – April 1, 1917) was an African-American composer and pianist.

Joplin achieved fame for his ragtime compositions, and was later titled The King of Ragtime. During his brief career, he wrote 44 original ragtime pieces, one ragtime ballet, and two operas. One of his first pieces, the Maple Leaf Rag, became ragtime’s first and most influential hit, and has been recognized as the archetypal rag.[2]Joplin was born into a musical family of laborers in Northeast Texas, and developed his musical knowledge with the help of local teachers, most notably Julius Weiss. Joplin grew up in Texarkana, where he formed a vocal quartet, and taught mandolin and guitar. During the late 1880s he left his job as a laborer with the railroad, and travelled around the American South as an itinerant musician. He went to Chicago for the World’s Fair of 1893, which played a major part in making ragtime a national craze by 1897.

Joplin moved to Sedalia, Missouri, in 1894, and earned a living as a piano teacher, continuing to tour the South. In Sedalia, he taught future ragtime composers Arthur Marshall, Scott Hayden and Brun Campbell. Joplin began publishing music in 1895, and publication of his Maple Leaf Rag in 1899 brought him fame. This piece had a profound influence on subsequent writers of ragtime. It also brought the composer a steady income for life, though Joplin did not reach this level of success again and frequently had financial problems.

Joplin moved to St. Louis in 1901, where he continued to compose and publish music, and regularly performed in the St Louis community. By the time he had moved to St. Louis, he may have been experiencing discoordination of the fingers, tremors, and an inability to speak clearly, as a result of having contracted syphilis. The score to his first opera, A Guest of Honor, was confiscated in 1903 with his belongings, owing to his non-payment of bills, and is considered lost by biographer Edward A. Berlin and others.

He continued to compose and publish music, and in 1907 moved to New York City, seeking to find a producer for a new opera. He attempted to go beyond the limitations of the musical form that made him famous, without much monetary success. His second opera, Treemonisha, was not received well at its partially staged performance in 1915.

In 1916, suffering from tertiary syphilis and by consequence rapidly deteriorating health, Joplin descended intodementia. He was admitted to a mental institution in January 1917, and died there three months later at the age of 49.

Joplin’s death is widely considered to mark the end of ragtime as a mainstream music format, and in the next several years it evolved with other styles into jazz, and eventually big band swing. His music was rediscovered and returned to popularity in the early 1970s with the release of a million-selling album of Joplin’s rags recorded byJoshua Rifkin, followed by the Academy Award–winning movie The Sting, which featured several of his compositions, such as The Entertainer. The opera Treemonisha was finally produced in full to wide acclaim in 1972. In 1976, Joplin was posthumously awarded a Pulitzer Prize.

- King Cotton – The expression “King Cotton” is often used to describe the cotton industry (and its tremendous importance) in the South during the antebellum period of American history. Following the invention of the cotton gin in 1793 by Eli Whitney, the cotton industry became the economic backbone of the southern economy and, as the result of the commanding role cotton began to play in foreign trade, stimulated the entire national economy. In 1850, for example, the American cotton crop was valued at more than $100 million annually, representing nearly fifty percent of all American export trade

Concurrent with the rise of King Cotton to a position of economic dominance in the South, African American slavery was given a new lease on life. Furthermore, as the cotton industry expanded between 1800 and 1860, so too did the institution of slavery. Despite federal laws and notwithstanding individual state regulations concerning both the Atlantic and domestic slave trade, the importation and selling of black African slaves increased proportionate to the labor demands of southern cotton plantations during- the first half of the nineteenth century. As the result of the importance of cotton to the southern, national and international economies, many southerners assumed that the North would be foolhardy to attempt any disruption of the industry (and concurrently slavery) for fear of economic chaos and foreign intervention. In 1858, for example, Senator James H. Hammond of South Carolina warned his northern colleagues not “to make war on cotton. No power on earth dares to make war upon it. Cotton is King.” See also: COTTON GIN.

- Little Rock Crisis – The so-called Little Rock Crisis of 1957 was one of the earliest and certainly most publicized attempts to enforce court-ordered school integration in the South. Early in 1957, the Little Rock, Arkansas school board had agreed to comply with a court-order demanding that the city’s Central High School admit black students. Nine carefully selected black children were chosen to begin classes at Central on September 4. In the meantime, however, Governor Orval Faubus assumed the stance of a diehard segregationist by intervening and defying the court-order. Following a dramatic television appearance, Faubus called out the National Guard to prevent the nine black youngsters from entering the previously all-white school. A federal court then ordered that the students be admitted and, concurrently, ordered that the National Guard be withdrawn

On September 23, the black children returned to Central only to be met with the curses and stones of an angry white mob. This mob violence prompted President Dwight D. Eisenhower to federalize the Arkansas National Guard and to send in paratroopers to restore order and escort the black students to and from school for the remainder of the year. Faubus reacted by closing the Little Rock schools for the academic year, 1958-59. A federal court subsequently ruled that Faubus’ action was unconstitutional, and thereby paved the way for the reopening of schools on a desegregated basis in the autumn of 1959.

- Middle Passage – The actual transatlantic voyage of slavers (slave ships) loaded with human cargo historically has been referred to as the “Middle Passage.” The term is derived from the fact that the transatlantic trip was the second leg or part of the overall slavetrading journey — from home port to Africa, from Africa to the New World, and from the New World to home port.

At best, the Middle Passage was an incredibly harsh experience for the hapless Africans unfortunate enough to have been sold into slavery in Africa. The voyage itself was time-consuming, ranging from three or four weeks to as long as three months, depending on the winds and currents. The Africans were not considered to be “passengers,” but rather cargo. As such, they were packed into the holds of slavers as if they were little more than black sardines. Sexually separated, chained slaves were forced to lie side-by-side in the hold for at least fifteen hours daily. When the typical hold of a slaver (which averaged about five feet in height) was divided into two “levels” or “floors,” the space allotment for each individual slave was approximately 6′ x 16″ x 21/2′ (essentially the dimensions of a coffin). Slaves were allowed on deck only to eat, to take part in forced physical exercise (“dancing the slaves,” as it was called) and to allow time for the cleaning of the hold. Considering the lack of sanitary facilities aboard, this job (which was rotated among the slaves themselves) was considered to be an especially unattractive feature of the voyage.

Historians are fortunate that several first-hand accounts written by slaves concerning the nature of the Middle Passage have survived. One account, penned by Olaudah Equiana, is especially illuminating: “I was soon put down under the decks, and there I received such a salutation in my nostrils as I had never experienced in my life: so that with the loathsomeness of the stench, and crying together, I became so sick and low that I was unable to eat, nor had I even the desire to taste anything. I now wished for the last friend, death, to relieve me. This wretched situation was again aggravated by the galling of the chains … the filth of the necessary tubs, into which the children often fell, and were almost suffocated, the shrieks of the women, and the groans of the dying… rendering the whole scene of horror almost inconceivable.”

It is not surprising that many slaves procured in Africa did not survive the Atlantic voyage. Smallpox, scurvy and suicide all took their toll. A large proportion of those who did survive the Middle Passage, according to historian John Hope Franklin, were unfit for slave-labor upon arrival in the New World. “Many of those that had not died of disease or committed suicide by jumping overboard,” Franklin maintains, “were permanently disabled by the ravages of some dread disease or by maiming which often resulted from the struggle against the chains.”

- National Black Political Convention – The first National Black Political Convention was held in Gary, Indiana in March 1972. Attended by over three thousand voting delegates and another five thousand observers, the Convention failed to resolve differences between those blacks content to work within the traditional two-party American political system and those desiring to create an independent black party. Other differences which tended to disrupt the conclave were those over integration and political cooperation with whites. Among resolutions which passed were those calling for radical socioeconomic changes in American society; a condemnation of American policy toward the white regimes of South Africa and Rhodesia; a denunciation of busing as a means of achieving racial balance in the public schools; and a refusal to endorse any candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination. Similarly, the second National Black Political Convention was characterized by continued argumentation about the desirability of a separatist political party. Held in Little Rock, Arkansas in March 1974, a resolution calling for the establishment of a national black political party was defeated; the NAACP and National Urban League were criticized for not sending representatives to the Convention; a resolution urging the creation of a black “united fund” with the goal of raising $10 million by 1976 was passed; and African liberation movements were given a blanket endorsement.

- Octoroon – The term octoroon referred to a person with one-eighth African ancestry;[3] that is, someone with family heritage of one biracial grandparent, in other words, one African great-grandparent and seven Caucasian great-grandparents. As with the use of quadroon, this word was applied to a limited extent in Australia for those of one-eighth Aboriginal ancestry, in the putting in place of government assimilation policies.

- PARTUS SEQUITUR VENTREM – The primary legal principle used to perpetuate African American slavery from one generation to another was that of partus sequitur ventrem, meaning that the child inherits the status or condition of the mother. Running contrary to the English tradition which determined the status of children according to the status of the father, partus sequitur ventrem ensured that African American slavery would continue indefinitely. Children of two slave parents, of course, would automatically be classified as slaves. Concurrently, a child born of an interracial union between a free white man and a black slave woman would also be classified as a slave. On the other hand, a child born of an interracial union between a free white woman and a black male slave would legally be free, inheriting the status of its mother. Since miscegenation between free white women and black slave males was relatively rare in the antebellum South, the products of such unions were numerically fewer than the children born of free white fathers and black slave mothers.

- Quock Walker Case – In large part the result of the realization that African American slavery was ideologically inconsistent with the goals and rhetoric of the American Revolution, northern states took the lead in abolishing slavery or otherwise providing for the gradual emancipation of slaves during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. In some states, such as Vermont, constitutions were written or legislation enacted which specifically outlawed slavery and the slave trade. In Massachusetts, however, slavery was gradually ended as the result of judicial interpretation and action. The most significant of several “freedom cases” leading to the death of slavery in Massachusetts was that of Commomvealth v. Jennison, commonly referred to as the Quock Walker Case of 1783. Quock Walker allegedly was the slave of one Nathaniel Jennison, who had forcibly captured his “slave” following an abortive runaway attempt. Jennison, in turn, was indicted by a local court for committing assault and battery on Walker. The case was subsequently appealed to the supreme court of Massachusetts in 1783. In his charge to the jury, Chief Justice William Gushing rejected Jennison’s argument that his actions constituted legitimate means of apprehending a runaway slave on the basis that Jennison had earlier promised to manumit Walker. More significantly, Gushing held that although slavery indeed had been tolerated in Massachusetts, it was incompatible with the revolutionary spirit “favorable to the natural rights of mankind.” Gushing concluded his charge by asserting that “slavery is inconsistent with our own conduct and Constitution; and there can be no such thing as perpetual servitude of a rational creature, unless his liberty is forfeited by some criminal conduct or given up by personal consent or contract.” The jury concurred with Cushing’s argument, upholding the indictment of Jennison.

- John B. Russwurm – One of the first blacks to graduate from an American college, John Brown Russwurm (1799-1851) was the son of a Jamaican mother and a white American father.

Born in Jamaica, Russwurm was taken as a youth to Canada and, later, to Maine, where he was educated. Graduating from Bowdoin College (Maine) in 1826, he soon traveled to New York City where he and Reverend Samuel Cornish founded and edited Freedom’s Journal, the first black newspaper in the United States. Following a dispute with Cornish over editorial policy concerning the merits of African colonization for American blacks (Russwurm was convinced that colonization offered Afro-Americans the best chance for survival), the young college graduate dissolved the partnership and migrated to Africa himself in 1829. From 1830 until his death twenty-one years later, Russwurm served in a number of official capacities in Liberia, the African colony founded by the American Colonization Society for repatriated African Americans.

Namaste.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.