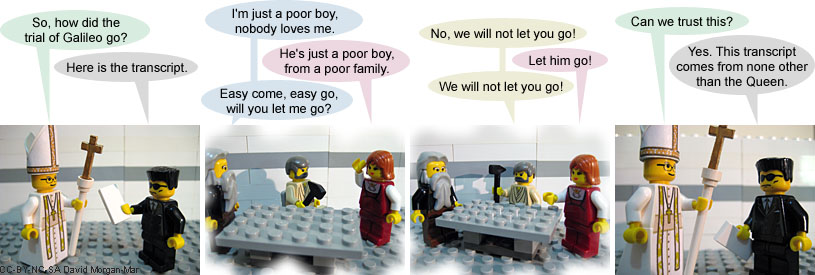

“O-E-O-E-O!”

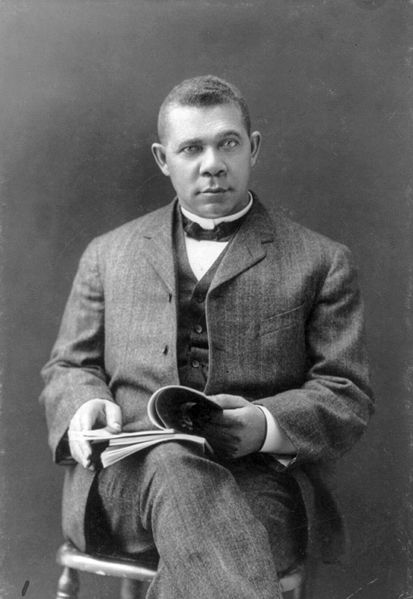

arts and leisure, everyday glory, family and friends, food for thought, games, geekery, monkeys!, news and info, office antics, style, Whiskey Tango Foxtrot...?! No Comments »Happy Birthday to

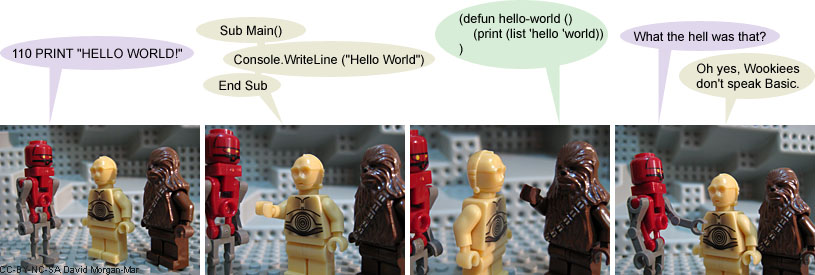

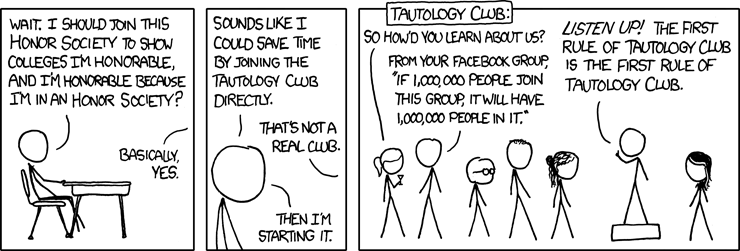

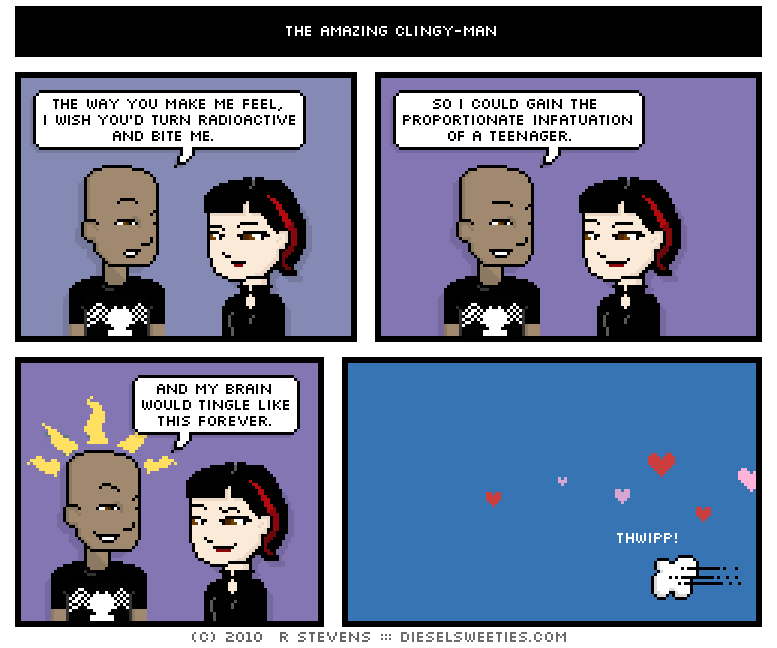

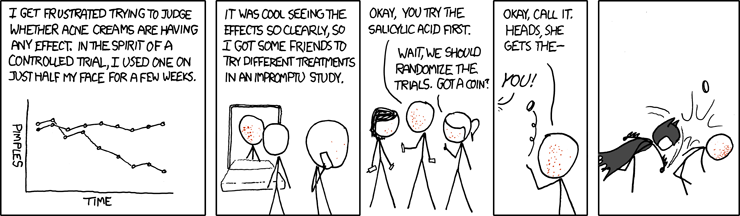

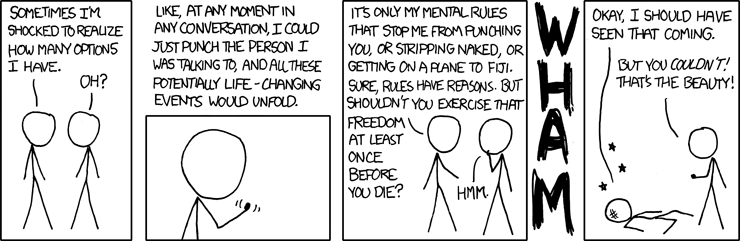

Today would ordinarily be Comics and Sushi Wednesday, but I’m in the south office again today. So, I’m just going to combine things and make tomorrow NBN Comics (and maybe Sushi) Thursday. Win-Win(-Win).

Chew on This: Food for Thought – Black History Month

Today, we shine the spotlight on Malcolm X:

Malcolm X – born Malcolm Little, and also known as El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz – was an African-American Muslim minister, public speaker, and human rights activist.

Born in Nebraska, while an infant Malcolm moved with his family to Lansing, Mich. When Malcolm was six years old, his father, the Rev. Earl Little, a Baptist minister and former supporter of the early black nationalist leader Marcus Garvey, died after being hit by a streetcar; his father’s lessons concerning black pride and self-reliance and his own experiences concerning race, played a significant role in Malcolm’s adult life. After his mother was committed to an insane asylum in 1939, Malcolm and his siblings were sent to foster homes or to live with family members.

Malcolm attended school in Lansing, Mich., but dropped out in the eighth grade when one of his teachers told him that he should become a carpenter instead of a lawyer. Years later, Malcolm would laugh about the incident, but at the time it was humiliating — It made him feel that there was no place in the white world for a career-oriented black man, no matter how smart he was. Malcolm became involved in hustling and other criminal activities in Boston and New York.

In 1943, the U.S. draft board ordered Little to register for military service. He later recalled that he put on a display to avoid the draft. Military physicians classified him as “mentally disqualified for military service”. He was issued a 4-F card, relieving him of his service obligations.

In 1946, Malcolm was sentenced to eight to ten years in prison. While in prison for robbery from 1946 to 1952, he underwent a conversion that eventually led him to join the Nation of Islam, an African American movement that combined elements of Islam with black nationalism. Following Nation tradition, he replaced his surname, “Little,†with an “X,†a custom among Nation of Islam followers who considered their family names to have originated with white slaveholders. On August 7, 1952, Malcolm X was paroled and was released from prison. He later reflected on the time he spent in prison after his conversion: “Months passed without my even thinking about being imprisoned. In fact, up to then, I had never been so truly free in my life.

After his release from prison Malcolm helped to lead the Nation of Islam during the period of its greatest growth and influence. He met Elijah Muhammad in Chicago in 1952 and then began organizing temples for the Nation in New York, Philadelphia, and Boston and in cities in the South. For nearly a dozen years, he was the public face of the Nation of Islam; Malcolm X promoted the Nation’s teachings – he taught that black people were the original people of the world, and that white people were a race of devils. In his speeches, Malcolm X said that black people were superior to white people, and that the demise of the white race was imminent.

While the civil rights movement fought against racial segregation, Malcolm X advocated the complete separation of African Americans from white people. He proposed the establishment of a separate country for black people as an interim measure until African Americans could return to Africa. Malcolm X also rejected the civil rights movement’s strategy of nonviolence and instead advocated that black people use any necessary means of self-defense to protect themselves. Many white people, and some blacks, were alarmed by Malcolm X and the things he said. He and the Nation of Islam were described as hatemongers, black segregationists, violence-seekers, and a threat to improved race relations. Civil rights organizations denounced Malcolm X and the Nation as irresponsible extremists whose views were not representative of African Americans.

Malcolm X was equally critical of the civil rights movement. He described its leaders as “stooges” for the white establishment and said that Martin Luther King, Jr. was a “chump”. He criticized the 1963 March on Washington, which he called “the farce on Washington”. He said he did not know why black people were excited over a demonstration “run by whites in front of a statue of a president who has been dead for a hundred years and who didn’t like us when he was alive”.

In 1963 there were deep tensions between Malcolm and Eiljah Muhammad over the political direction of the Nation. Malcolm urged that the Nation become more active in the widespread civil rights protests instead of just being a critic on the sidelines. Muhammad’s violations of the moral code of the Nation further worsened his relations with Malcolm.

Malcolm left the Nation in March 1964 and in the next month founded Muslim Mosque, Inc. During his pilgrimage to Mecca that same year, he experienced a second conversion and embraced Sunni Islam, adopting the Muslim name el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz. Renouncing the separatist beliefs of the Nation, he claimed that the solution to racial problems in the United States lay in orthodox Islam.

The growing hostility between Malcolm and the Nation led to death threats and open violence against him. On Feb. 21, 1965, Malcolm was assassinated while delivering a lecture at the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem; three members of the Nation of Islam were convicted of the murder.

Stray Toasters

- It’s snowing outside. It seems to be warm enough that nothing’s sticking, though.

- US Navy moves to let women serve on submarines

- It’s Doodle Time!

- I have peanut M&M’s.

- New York Fashion Week 2010

- Writers’ Advice for Writers

- The Unbelievable World of Warcraft, courtesy of

- Trial date set for South Africa ‘racist’ student video

- Hacker Arrested in Billboard Porn Stunt

Experience slips away…

Experience slips away…

The innocence slips away.

Namaste.