“Me and my shadow…”

books, business and economy, comics and animation, everyday glory, food for thought, games, geekery, history, news and info, office antics, people, science and technology, travel February 2nd, 2011It’s Groundhog Day; be on the lookout for Bill Murray.

It’s also new comics day and D&D (4e) night, to boot.

Last night was D&D (3.5) night with

After I got home, I played DCUO for an hour or so. One of the missions repeatedly kicked my trash. Nothing like getting swarmed – and defeated – by higher-level H.I.V.E. Troopers…repeatedly. *sigh* After what felt like eleventy-kajillion times, I finally got through it. I did a couple of Brainiac-related missions, as well. Those weren’t quite as painful, though.

Chew on This: Food for Thought – Black History Month

Today’s person of note is… actually going to be TWO people:

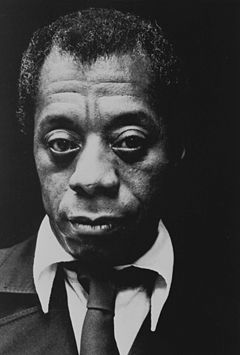

- James Baldwin

Baldwin was an American novelist, writer, playwright, poet,essayist and civil rights activist.

Most of Baldwin’s work deals with racial and sexual issues in the mid-20th century in the United States. His novels are notable for the personal way in which they explore questions of identity as well as the way in which they mine complex social and psychological pressures related to being black and homosexual well before the social, cultural or political equality of these groups was improved.

During his teenage years in Harlem and Greenwich Village, Baldwin began to recognize his own homosexuality. In 1948, disillusioned by American prejudice against blacks and homosexuals, Baldwin left the United States and departed to Paris, France. His flight was not just a desire to distance himself from American prejudice. He fled in order to see himself and his writing beyond an African American context and to be read as not “merely a Negro; or, even, merely a Negro writer”. Also, he left the United States desiring to come to terms with his sexual ambivalence and flee the hopelessness that many young African American men like himself succumbed to in New York.

In 1953, Baldwin’s first novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain, an autobiographical bildungsroman, was published. Baldwin’s first collection of essays, Notes of a Native Son appeared two years later. Baldwin continued to experiment with literary forms throughout his career, publishing poetry and plays as well as the fiction and essays for which he was known.

Baldwin’s second novel, Giovanni’s Room, stirred controversy when it was first published in 1956 due to its explicit homoerotic content. Baldwin was again resisting labels with the publication of this work: despite the reading public’s expectations that he would publish works dealing with the African American experience, Giovanni’s Room is exclusively about white characters. Baldwin’s next two novels, Another Country and Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone, are sprawling, experimental works dealing with black and white characters and with heterosexual, homosexual, and bisexual characters. These novels struggle to contain the turbulence of the 1960s: they are saturated with a sense of violent unrest and outrage.

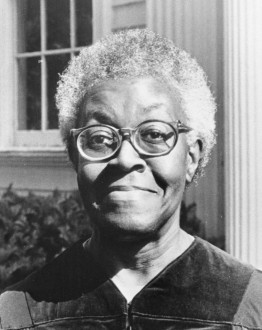

- Gwendolyn Brooks

Gwendolyn Elizabeth Brooks was an American writer. She was appointed Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress in 1985.

Brooks published her first poem in a children’s magazine at the age of thirteen. When Brooks was sixteen years old, she had compiled a portfolio of around seventy-five published poems. Aged 17, Brooks stuck to her roots and began submitting her work to “Lights and Shadows”, the poetry column of the Chicago Defender, an African-American newspaper. Although her poems range in style from traditional ballads and sonnets to using blues rhythms in free verse, her characters are often drawn from the poor inner city.

Her first book of poetry, A Street in Bronzeville, published in 1945 by Harper and Row, brought her instant critical acclaim. She received her first Guggenheim Fellowship and was one of the “Ten Young Women of the Year” in Mademoiselle magazine. In 1950, she published her second book of poetry, Annie Allen, which won her Poetry magazine’s Eunice Tietjens Prize and the Pulitzer Prize for poetry, the first given to an African-American.

After John F. Kennedy invited her to read at a Library of Congress poetry festival in 1962, she began her career teaching creative writing. She taught at Columbia College Chicago, Northeastern Illinois University, Elmhurst College, Columbia University, Clay College of New York, and the University of Wisconsin–Madison. In 1967, she attended a writer’s conference at Fisk University where, she said, she rediscovered her blackness. This rediscovery is reflected in her work In The Mecca, a book length poem about a mother searching for her lost child in a Chicago housing project. In The Mecca was nominated for the National Book Award for poetry.

In addition to the National Book Award nomination and the Pulitzer Prize, Brooks was made Poet Laureate of Illinois in 1968. In 1985, Brooks became the Library of Congress’s Consultant in Poetry, a one year position whose title changed the next year to Poet Laureate. In 1988, she was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame. In 1994, she was chosen as the National Endowment for the Humanities’ Jefferson Lecturer, one of the highest honors for American literature and the highest award in the humanities given by the federal government. In 1995, she was presented with the National Medal of Arts.

Stray Toasters

- Consider this: There is almost always enough time to exchange a pleasantry with a coworker before asking a question or setting them to a task. It amuses me how often I have to “gently remind” people of this fact.

- Flowchart: What Facebook Comment Should You Leave?

- I considered making Avery Brooks (1, 2) this morning’s Black History Month personality… but then I figured that people might not want to read my gushings over my man-crush. So, I didn’t.

But, guess what: You’re reading about him, anyway! So, I guess that means I still win!

- Punxsutawney Phil celebrates 125 years of Groundhog Day

- How to Use “Who” and “Whom” Correctly

- Fees for home mortgages increase

- Crime Scenes: No break for cops caught on camera

- A Hacking Case Becomes a War of the Tabloids

- Batman: billionaire plutocrat vigilante

- Leave the libraries alone. You don’t understand their worth.

Namaste.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.